Re-Introduction

I want to open up this article by explaining where I’ve been for the past few months. I have not been writing since my winter break from college, primarily because my 2nd semester of school was incredibly difficult and stressful. However, now that I am on the other side of it, I can happily say that I will hopefully be finishing this article series this summer.

In the Snow Covered Valley

New Years Day, 1945 was a day met with little fanfare back home. Although the significance of the date was noted, and the usual drinks and celebrations went on, there was a tinge of something else present as 11:59 PM, December 31, 1944, turned into January 1, 1945. Perhaps that something else was fear for family overseas. As Robert Dexter Jones of 24 Charles Street could tell you, that fear was entirely warranted.

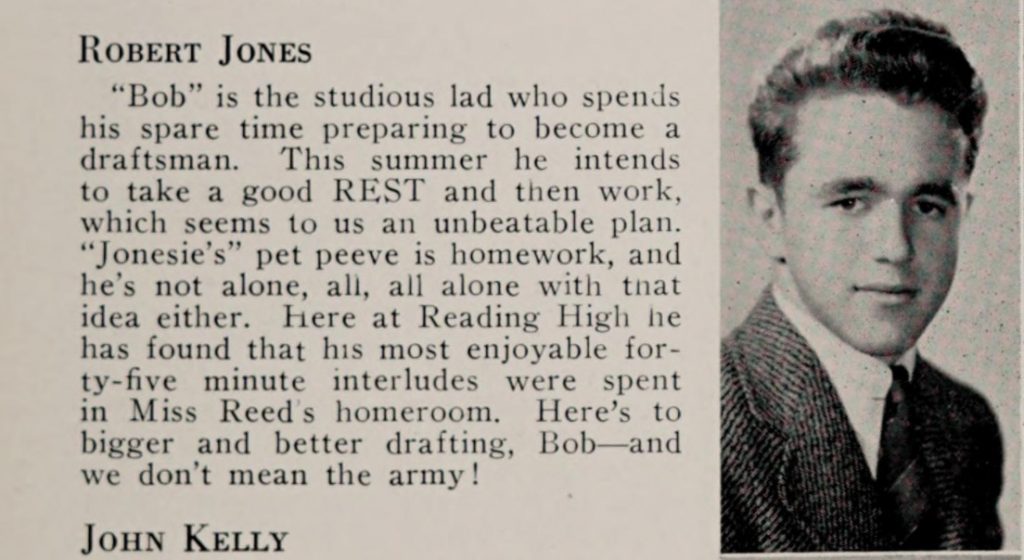

Born on November 29, 1922, Robert would graduate from Reading High School with the class of 1941, which would promptly be ushered into wartime. Rather luckily for Robert, the draft wouldn’t take him until January 22, 1943. The handsome young Jones would end up getting assigned to Company A of the 276th Infantry Regiment, 70th Infantry Division. This, too, was quite a lucky assignment, seeing as the 70th Infantry Division didn’t head overseas until December of 1944, as I discussed in my last article.

After arriving on the European continent earlier that month, Robert finally got his first orders to begin the trek up towards frontline duty on December 29, 1944. Their destination would be a sector along the Rhine River close to the villages of Seltz and Roschwoog, with the job of manning defensive foxholes along the river. The fact that Robert and his friends had seen literally no other American forces on their way here also left the impression that they were very much alone. It left an eerie taste in the mouth. To make matters worse, many of the men were apprehensive about the townspeople. Seeing as they were stationed in Alsace, it was quite possible that many of the people around them were more loyal to the Germans than they were to France. In fact, when the village rang their bells to gather the townspeople to tell them the latest news, many of the GIs complained to superiors that they could be trying to “signal the enemy.”

There were many scares during the days watching the Rhine, including two enemy aircraft swooping low enough that a patrol feared they may have been spotted by the planes. The first casualty that Company A would suffer during the war would occur during one of these scares, a few hours after dark on New Year’s Eve, when a German patrol crossed the river and began attacking a forward outpost manned by Sergeant John Cummings. The man was alone in his foxhole when the Germans began spraying the ground with automatic weapons fire. Perhaps it was Robert that was the one that heard the Sergeant’s BAR spring into action because the whole company was under the impression that they had certainly heard a BAR, surely Cummings’s, return fire. When John’s friends rushed forward to his foxhole, they found it empty. All that was left was a bloody steel helmet belonging to Cummings, with one bullet hole in the center. Upon further investigation, the men found more blood in the foxhole and more about twenty feet away from it, suggesting that perhaps Cummings hit at least one soldier before he himself fell. The problem was that no bodies were found, nor was Cummings’s BAR, and there was far too much blood to truly believe that Cummings could have been captured.

In 2018, the mystery of what happened to John Cummings, a young man from the state of Wisconsin, was laid to rest in some way. Shortly after the war had ended, American authorities found out about a young man buried in a nearby village of Iffezheim, Germany. Thanks to DNA testing, they were able to determine that the remains in the grave were those of John Cummings, and he was finally returned home to Wisconsin. It is unknown to me if Robert was a friend of John’s, but I cannot imagine a situation in which Robert would not have known who John was. Even in Robert’s death in 2010, I hope this small piece of knowledge that John finally made it home as he did, brings happiness.

Not long after arriving in Oberhoffen, the men of Company A were once again ordered to haul their gear up into trucks for another drive. This time, the drive came on the dreary morning of January 2, under dark gray skies. In the late hours of the afternoon, Robert and the rest of the company arrived in the small French village of Zittersheim, near the Moder River, a light snow greeting them. The mission of the 276th Infantry Regiment was to occupy and defend positions from Volksberg to Ingwiller in the Les Vosges mountains. Robert’s Company A, of the First Battalion, was assigned to a reserve position south of the village known as Wingen-sur-Moder, a village whose name was likely burned into Robert’s brain.

After a three-mile march through deep snow and a thick forest, Company A settled down for the night, south of Wingen-sur-Moder. All was quiet until midnight when a German patrol was spotted moving in a clearing to the north. Thankfully, a single shot from the American sentry frightened off the patrol, who disappeared and weren’t seen again. As the sun came up on January 3, Robert was ordered to move up with the rest of the company to establish defensive positions out of the woods in a snow-covered field, 200 yards south of Wingen. Emerging from the forest, many men set their eyes upon what appeared to be the most beautiful Christmas scene they had ever witnessed. Smoke rising from some homes’ chimneys, sitting in a village in a valley…it was beautiful. The men were quickly ordered to dig in rather than take in the sight before them. Robert did as he was told, likely digging a foxhole for himself and another man. However, this task was incredibly difficult because of the…err, frozen nature of the ground. Funnily enough, as darkness set in, the men were informed that they could return to the forest they had come out of for cover instead of sitting in poorly dug foxholes in an open field. Naturally, it was in the early hours of the next morning, January 4, that all hell broke loose.

Machine guns sprayed the open snow-covered fields in front of the forest. Enemy flares lit up the sky as they drifted down, casting eerie shadows through the forest and fields. The men of Company A had been told that they were held in reserve. The front line wasn’t remotely close enough to them for them to believe what they were seeing, or so everyone thought, because it became clearly apparent in the terrified, waking moments of Robert Jones and his buddies that the frontline had moved to Wingen-sur-Moder. Germans were in the streets before the American GIs had fully rubbed sleep from their eyes. In the ensuing nightmare, Company A lost communications with all other companies. The Commanding Officer of the unit was relying on their runner, Private First Class Eddie Tsukimura, to get messages from Company A to the rest of the regiment. Captain Hendrickson dispatched him to the Battalion HQ to report the attack, and Eddie returned in less than an hour with orders to dig in and hold the line. By 9:00 AM that morning, the German Army had completely captured the sleepy little picturesque village. The 276th Infantry Regiment’s intelligence informed Company A that it was likely that the enemy troops before them numbered no more than fifty and no less than thirty and that they were likely starving and low on ammunition.

The inevitable order to move up and re-occupy those shallow foxholes that the company had attempted to dig the day before came down, and Company A prepared for a fight to get to those shoddy holes. As the men moved up to try to retake the positions, they met heavy enemy opposition from the village and its cemetery that overlooked the field. In fact, two of the foxholes the company had dug were now occupied by German soldiers. Getting down on their bellies, some men began to crawl through the deep snow towards their foxholes. As the men re-entered their foxholes after much commotion, a German sniper from the bell tower of the church that overlooked the village began firing at them, pinning them down firmly where they were, unable to move at all. It is likely that during the period that followed this, in which two enemy machine gunners began covering the open field with fire, that Robert witnessed an act of heroism that would, unfortunately, fall short and cost Company A its first officer, Lieutenant McClintock, who had tried to run forward and toss a grenade towards the enemy gunners but was cut down. As the afternoon set in, many of the men began to realize, with a start, that they were running low on ammunition, and even worse, they didn’t have many rations left, either, along with their canteens full of water being completely frozen. That evening, under cover of darkness, men from the rear platoons snuck forward with rations and ammunition and helped the wounded men to safety. During the night hours, a German patrol attempted to sneak in between the GI foxholes but was taken out.

Finally, the next day began, and the horrible day that had been January 4, 1945, ended. During the early hours of the morning, a patrol was sent out to search for Company B. Upon arriving near the area where Company B was supposed to be, the Americans of Company A found only German soldiers. Apparently, earlier that evening, the company had been attacked in force from behind and was completely destroyed. Suddenly, the whole thing about the Germans in and around the village being just a few hungry and under-equipped soldiers seemed…unlikely.

On the morning of January 5, at around 8:00 AM, Robert and his fellow soldiers led an attack on the village of Wingen, with the men in the foxholes in the open field staying put and distracting the enemy while the rear troops came around the side to flank the enemy. This was going well until the men got into the village and met such severe enemy fire that they could not advance or fall back at all. In the heat of the battle, I can just picture Robert cheering and hitting his buddies on the arms from their spot on the ground at the sight of a friendly tank appearing in the distance. These tanks of the 781st Tank Battalion, 14th Armored Division, had been recently assigned to Company A. One of the men who would move forward with the tank was a man by the name of Earl Granger, who would be wounded badly in the leg while crawling up a ditch. That wound would be Earl’s third Purple Heart: his first came at the bombing of Pearl Harbor, and his second had come at Guadalcanal. During the fighting, a grenade thrown by a young GI landed in the basement of a home that saw 13 Germans run out. No sooner had they run out, a tank shell took out the entire front side of the building. It must have been a massive relief to watch that house explode. All of a sudden, Robert and his friends weren’t stuck there without help or heavy weapons. Now they had a mighty American Sherman rolling down the main street of Wingen-sur-Moder. With Captain Hendrickson gone, after being evacuated with serious chest wounds, a First Lieutenant Howard Arnest took command of Company A, and among the men, it was generally agreed that Arnest did not ask anything of them that he would not be willing to do himself.

It was not until after the men of Company A and the rest of the 276th Infantry Regiment had recaptured the town of Wingen-sur-Moder, that they learned what they had actually faced. Rather than facing 50 German Wehrmacht soldiers, nearly out of ammunition and starving, they had taken on nearly 900 soldiers of the 12th Mountain Regiment, 6th SS Mountain Division. Until recently, that unit had seen fighting exclusively on the Eastern Front and had not yet been defeated. In fact, they had come all the way from the Eastern Front, especially for this operation. As night fell on January 5, Lt. Arnest began trying to determine how to get the wounded men out and ammunition in. Many attempts to bring in ammunition earlier that day had failed miserably, and there were no signs that it would suddenly become easier under cover of darkness. Shortly before dusk that day, two more Sherman tanks appeared in the distance and were greeted with much excitement. Soon after, the 2nd Battalion of the 274th Infantry Regiment, 70th Infantry Regiment, began attacking the village in force. The prayers of so many Company A men had been answered as those fresh boots stepped into Wingen.

Although the men of Company A were allowed to reoccupy their positions outside of Wingen now that the 274th Infantry had arrived, they still did not have any official relief, and thus, Robert Jones, in his blood-stained and torn uniform, covered in grime, nearly out of ammunition, and starving, hauled himself back into that same old foxhole he had been in when this whole thing started. So, with the enemy constantly probing into their lines, Company A settled down for the night. For days, the fighting continued, and Company A was almost completely pinned down in their field outside of town while other men took on the Germans still inside the village. Finally, one cold morning, the Germans left the village, and Robert and the rest of his company were given permission to abandon their foxholes and return to the woods to try to get warm. It was around this time that many men were wondering just how in the hell they had survived such a slaughter.

The morning of January 9, the men of Company A were finally relieved for real. For the first time in weeks, Robert finally got a chance to have a shower and a hot meal. But the best part of that day was probably when the company’s mailman delivered their letters, many of which had been piling up since Christmas. Their rest would be short-lived, though, because, on the evening of January 10, 1945, the company was once again alerted for movement and sent up the line for an attack.

This attack really was in the middle of nowhere because it was designed to keep the Germans from breaking through a lower mountain pass. The terrain was so rough that most of the men of the 276th Infantry Regiment kept their rifles slung over their shoulders, so their hands were free to climb. The fighting in the woods was fierce and incredibly scary because the Germans with their white parkas were difficult to see against the bleach-colored snow. Thankfully, though, despite the heavy fighting, the now combat-experienced unit made it out, although they paid quite a lot for it.

Robert was still safe, and the rest of January 1945 saw him and his buddies recovering from the fighting they had experienced in Wingen and the mountains. His family back home may have even received a letter from him during the middle or latter half of the month and were filled with joy to hear from their son.

On the Edge of the Woods

After the heavy combat that Joseph Warren Keenan would see as the commanding officer of Company L, 329th Infantry Regiment during December, his men would receive a much-needed break. On New Year’s Day, they were actually resting…it was a nice change of pace, I imagine. Interestingly, on December 31, 1944, Joseph was actually relieved of the job of commanding officer of Company L. It is unknown why he was relieved of this duty, but it doesn’t seem like he did anything wrong that I can find.

As is often the case with times of rest for frontline soldiers, the period did not last, and on January 3, Joseph and his company were heading towards the frontline to relieve the famed 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment of the 82nd Airborne. Although they were not yet engaged in combat, the men of the 329th Infantry Regiment were currently fighting a war with Mother Nature as the snow in their area began to deepen, and the temperatures continued to drop.

I kind of wonder how Joseph handled all of the complaints about the cold that he got from the men he commanded, which was now limited to just a platoon rather than the entire company. He was from Roxbury before the war, after all, so he was no stranger to the cold (despite this weather being much colder than anything he would have experienced). In my opinion, Joseph probably went one of two ways: either he was very sympathetic, understanding that many of his men probably were not used to the cold and tried to give them ways to keep themselves warm, or he was just so used to the cold that he told them to stop whining. Either way, the cold was definitely a powerful enemy that needed to be considered.

For the coming attack, Joseph and his company were lined up to the right of the 329th Infantry. The first objective of the attack that jumped off on January 10 at 8:00 AM, with the temperature striking zero degrees, would be the town of Petite Langlir. The terrain surrounding the village was almost entirely wooded, providing good cover…but much like the dilemma that Robert Jones ended up in, the area immediately outside of the village was just an open field on all sides.

At 8:00 AM, as Joseph and his men were getting ready to push forward, a sudden barrage of German artillery struck the area of the entire 3rd Battalion to which Joseph belonged and caused their advance to start 30 minutes late. Unfortunately, even once they got going, they were stopped at the edge of the woods because of crippling enemy fire. In the hours that followed, I can imagine Joseph wondering what he could possibly do to get his men forward without watching them get methodically mowed down. And honestly, just that thought at all– of having to understand the fact that you, the company commander, are distantly responsible for the deaths of the men you send forward, was probably enough to keep Joseph quiet about the war in the years after it. The attack was renewed the next day but was halted for the exact same reasons as the day before. Casualties were mounting in the 3rd Battalion, especially due to the presence of enemy tanks that were lobbing their shells into the forest where the men of Joseph’s company, as well as the other two companies, were taking shelter. It wasn’t until January 12, 1945, that the 3rd Battalion was given directions to enter the town of Petite Langlir the same way that some of the men of the 331st Infantry Regiment (of the same division as Joseph, the 83rd Infantry Division) had gone in. This ended up working, despite the enemy presence, and by the afternoon of the 12th, the entire 3rd and 2nd Battalions of the 329th Infantry Regiment were inside the boundaries of their first objective. Thankfully, all went well in the days after this, and the mission of the 329th Infantry Regiment had been successfully accomplished.

On January 30, 1945, Joseph Keenan would report in sick to the unit medic and would be sent to the hospital. It is again unknown what sickness he was experiencing, but he would not return to the 329th Infantry Regiment until February 9, 1945, and instead of rejoining Company L, he would join Company K as the unit’s commanding officer.

The Wood That Never Cleared

After the fighting that Harry Lincoln Beeth had seen in December, it is quite likely that Harry was as used to the cold as anyone could be (which wasn’t very much) by the time January rolled around. Much like Joseph Keenan, Harry Beeth was lucky to be resting on New Year’s Day. After a decent period of rest, a welcome exception to the rule that most of the men I have written about have demonstrated, Harry, who would live in Reading after the war had ended, would receive orders to move out with Company B, 23rd Tank Battalion, 12th Armored Division.

On January 14, a single platoon of 5 Sherman tanks from Harry’s Company B made a probing strike into an area near Ohlungen, France. During this escapade, the tanks came under heavy enemy fire and were forced to withdraw relatively quickly but still accomplished their job to attempt to get an idea of what the enemy positions in the area were like. In the next few days, Company B would be attached to the 66th Armored Infantry Battalion as the entire 12th Armored Division prepared for an attack towards Herrlisheim. The job of Harry’s unit would be to clear Stainwald, a forest outside of the aforementioned town.

It was in the morning hours of January 16 that this big attack was supposed to begin, but communication among the attacking units broke down. At some point in the morning, it was established that Company B had not successfully captured Stainwald. It is noted in the 23rd Tank Battalion’s unit history that Harry’s Company B, along with the 66th Armored Infantry, had managed to get into the forest but had immediately been pinned down by German machine guns. The tanks were also unable to advance because they discovered not long after trying to do so that they were surrounded by mines. As a tank commander during all of this, I can imagine Harry was probably chaotically yelling, “Stop! Stop! Mines, there are mines!” as he ducked into the top hatch to avoid being hit by German gunners. Eventually, the men had to withdraw– there was no progress being made that was worth the cost they were currently paying.

The next day, January 17, the same order reached Company B of the 23rd Tank Battalion and the 66th Armored Infantry: clear Stainwald. However, before they could begin their second attempt to take the wood, their orders were changed to bypass Stainwald and attack the village of Offendorf from the south. Just as the day before, Harry and his fellow soldiers woke around midnight and began their new attack at 2:30 AM. As the tanks began to head down the road, one of the officers asked them to stop and dismount first to try to clear out any mines on the road. Although it was an incredibly smart idea, the Germans could hear the sounds of the tankers hitting the ice around the mines to chop them out. Moments later, German artillery and mortar fire began landing among the men of Company B and the 66th Armored Infantry. It must have been pandemonium. If Harry hadn’t been one of the men to go help clear mines, he was probably yelling to his crew, “Run! Come on!” Once more, the entire task force had to withdraw.

Meanwhile, as all of this was happening outside of the woods, the men of the 17th Armored Infantry Battalion were being encircled and decimated in the city of Herrlisheim. They needed help, and they needed it fast. On January 18, the task force from before, with Harry in it, was ordered to make a dash towards Herrlisheim in an attempt to relieve pressure on the infantry. Almost as soon as they reached the area, the tanks were pushed back by intense German anti-tank fire.

Thankfully, on January 21, finally, the 23rd Tank Battalion and the rest of the 12th Armored Division were relieved. Although it may seem as though Harry didn’t see a whole lot of combat during this period, this is far from the truth. Harry and his comrades ended up bravely holding off dozens of motivated and deadly enemy soldiers and saving the lives of many infantrymen in the process.