Introduction

There is a quote that I found a long time ago while working on an idea for a short story that I would like to open up with here: “In war, our elders may give the orders…but it is the young who have to fight.” That was something written by T. H. White. I believe it to be particularly true when it comes to Operation Market Garden, the subject of this issue of Reading’s Boys.

After the successful landings on the beaches of Normandy, and after the liberation of Paris, the generals of the Allied forces were on something of a high. Their egos were rising too high, their goals too far from mortal grasp. The allied generals started to believe that the German Army might be on the brink of collapse. Within this environment of over-confidence and blind optimism, the idea for Operation Market Garden was born.

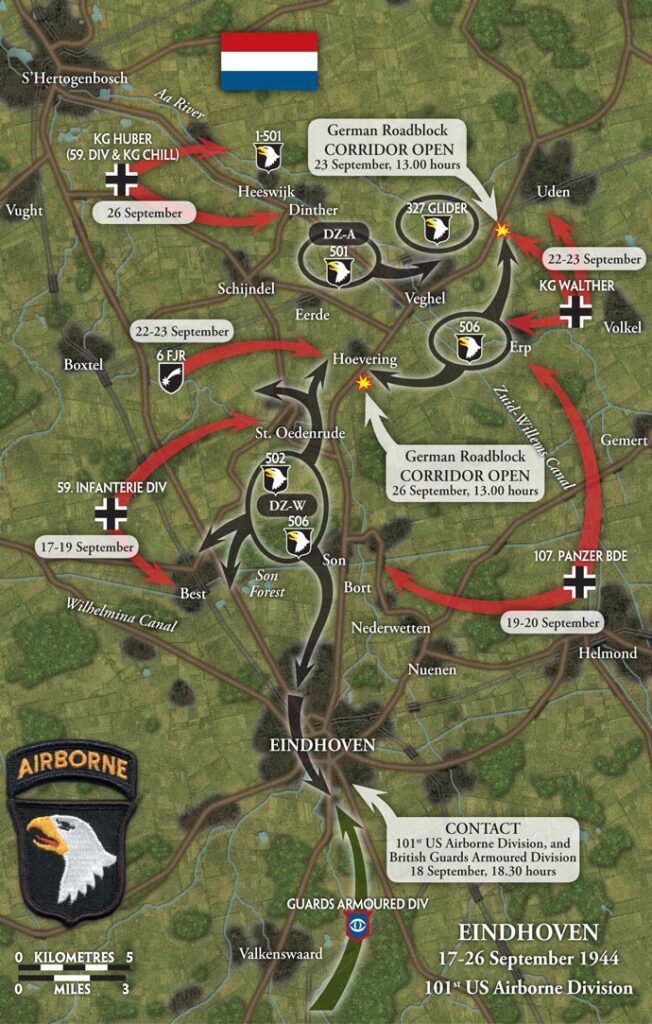

The plan was to drop three airborne divisions many, many miles behind enemy lines to capture a series of bridges, starting in Eindhoven with the 101st Airborne Division. Once the 101st Airborne Division captured their objectives, they would link up with the British XXX Corps who would push north from their lines and open a path to Eindhoven so that more infantry might be able to get in. The 82nd Airborne Division would be responsible for a series of bridges with arguably the most important one being Nijmegen. The hope was that the 101st Airborne Division, now with British Armor backing them up, would cross their bridge and make their way up to the 82nd Airborne Division to strengthen their ranks. Then the big one: Arnhem Bridge, to be captured by the 1st British Airborne Division. The water that ran beneath Arnhem Bridge was the water of the Rhine River.

Arne Helge Gunnar Dahlquist (August-September 1944)

Since finishing my last article that discussed the actions of Arne Dahlquist, I have learned that Arne may have actually been a member of the 320th Glider Field Artillery Battalion (the artillery battalion that directly supported the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment whenever possible) and was later transferred to the Headquarters Company of the 3rd Battalion, 325th Glider Infantry Regiment. It is my belief that Arne was a member of the 320th Field Artillery Battalion for the invasion of Normandy and then Operation Market Garden in September of 1944. There are a few reasons for my thinking on this subject, and though I won’t be explaining them here, I may do so at another point in time. With that aside, I will be telling Arne’s story here as though he was a member of the 320th Glider Field Artillery Battalion.

Once the 82nd Airborne Division returned to England after finishing up their operations in Normandy, to say that the men were exhausted would have been an understatement. For the next two months, Arne and the rest of the division would undergo intense training and physical conditioning. On September 15, 1944, everyone must have realized something was up because they had been closed into their bases the same way they had been in the lead up to their jump into Normandy. They would have gone over the plan over and over again as they waited to board their aircrafts. Now, although the 82nd Airborne Division would jump into Holland on September 17, the 320th Glider Field Artillery Battalion would not join them until September 18 and 19, coming in on gliders that were able to make their way through the fog that had kept much of the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment stuck in England.

On the morning of September 18, something was horribly wrong on the ground in Holland, though: the landing zones for the gliders were being overrun by German infantry. I imagine that some of the paratroopers on the ground couldn’t bring themselves to watch as our gliders came into land. General Gavin, one of the men in charge of the 82nd Airborne Division described watching the gliders come in, “The drone of the engines reached a roar as they came directly over the landing zones. I experienced a terrible feeling of helplessness. I wanted to tell them that they were landing right on the German infantry.”

So it seemed Arne was already set up for failure if he had come in with the 320th Glider Field Artillery Battalion that day as I believe he did. But then something happened, something so miraculous that it could have been pulled straight from an action movie: paratroopers of the 508th Parachute Infantry Regiment began charging into the field occupied by the Germans just as the friendly gliders began coming into land. This caused the Germans to panic for some reason, and they turned and ran. Glidermen were seen exiting their crafts after landing and firing on the Germans as they retreated. I wonder if, after the initial anxiety of the moment, some of the men stopped to laugh at the luck of it all. I can see Arne running through the field carrying parts of their artillery guns, yelling to the paratroopers, “Well geez, thanks guys!” with a broad grin.

As the sun rose the next day, the 82nd Airborne Division made first contact with the British tanks from XXX Corps. The Nijmegan bridge needed to be taken that day. There was no other way. If the bridge was not taken, the British 1st Airborne at Arnhem would collapse. They had already been surrounded since September 17 and had no supplies because the daily supply drops were actually dropping the supplies for the British right into the German lines. Now the best question to ask is, “Well, what’s the best way to take a bridge?” The answer is to take both sides at once, so a bold plan was put into place: a group of paratroopers would take small canvas boats provided by the British across the Waal River to take the German end of the bridge while the XXX Corps tanks pushed across the bridge to meet the infantry on the other side.

On September 20, at 2:00 PM, men of the 307th Airborne Engineer Battalion and the 504th Parachute Infantry Regiment began to cross the Waal River. It is likely that Arne would have been situated on the American-held shore with an artillery piece and crew, ready to fire. Perhaps he couldn’t bring himself to look at the paratroopers, huddled together in their boats, some paddling with the butts of their rifles. Or perhaps he couldn’t look away. Either way, I’m sure he felt that tightness in his chest, the feeling of adrenaline pumping through his veins. The men in those boats were sitting ducks and everyone knew it. All at once, the Germans on the opposite shore opened fire on the paratroopers. Machine guns were heard cracking through the afternoon air, tank shells whizzed overheads, and decimated boats. And I bet Arne watched it all happen.

At some point during all of this, Arne was actually wounded. I have no clue when it happened– for all I know, it could have been right on September 18 or it could have been as late as September 23, which also happened to be the day the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment was finally able to arrive after delays due to bad weather. Arne Dahlquist was hit in the shoulder by a fragment of an artillery shell. I can only imagine he would have keeled over and called for a medic. Perhaps there were men with him when it happened, and they tried to get him up to an aid station.

“Don’t look, Gunnar, just don’t look,” they may have said, using his nickname, “You’re fine. We’ve got you, you’re gonna be fine.”

Somehow, someway, we took that bridge, but it was too late. The 1st British Airborne at Arnhem had been cut off and absolutely destroyed. Operation Market Garden was a failure. The 82nd Airborne Division would end up holding the Nijmegen area until being relieved by the Canadians in November 1944.

Though I have no way to be sure, I believe that sometime between September 1944 and December 1944, Arne was probably transferred to the unit he would end the war with Headquarters Company, 3rd Battalion, 325th Glider Infantry Regiment. One way or another, Arne would come out on the other side of Operation Market Garden alive. The same cannot be said for Richard Austin…

Richard Charles Austin (August-September 1944)

Much like I did with Arne, I discovered some new and exciting information about Richard since the last time we heard about him: Richard was a member of Company B, 1st Battalion, 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division. This means that it is much easier for us to determine where he was during Operation Market Garden, and without any further delay, we will get right into that.

The return to England following the 101st Airborne’s operations in Normandy must have felt like quite a relief for many of the men. With a steady flow of replacements joining the division and a Presidential Unit Citation on the horizon for action in Normandy, the unit was recovering. I imagine that many of the men who had survived the jump into Normandy as Richard had now felt unable to relate to the fresh troops that were refilling their ranks. At the age of 21, Richard would have been looked at by the replacement troops as a hardened and experienced veteran.

When the orders reached the 101st Airborne Division that they would be jumping into Holland in September, reactions were probably mixed. Maybe Richard would have collected himself, sat down, and written a letter home to clear his mind. Perhaps he secretly hoped, as many other men did, that the mission would be called off as some of their others had been. This mission would go forward, though. Around 9:00 AM on September 17, 1944, the men of the 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment began heading for their transport planes.

I wonder what was running through Richard’s head as he boarded his plane. Was he feeling optimistic? He had been through this once before, and he had survived. Perhaps he could do it again. Or maybe he was feeling worried. He may have asked himself, “Has my luck finally run out?” The flight to Holland was beautiful. The sky was clear and the sun was shining. That green light would have switched on in Richard’s plane and every man would have gone through the door. As Richard floated down to the earth, he may have been surprised that they were not being fired upon. It was like something out of a fairytale. The men just gently floated to the ground.

If you look at the map provided, you can see that the 1st Battalion of the 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment was assigned a drop zone near Eerde. The job of the 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment was to capture the bridges at Veghel. Unfortunately for Richard’s battalion, though, they had landed five miles north-west of where they had been supposed to land and they now had to form up and try to make their way to their original planned drop zone. Richard’s company, Company B, was selected to be the advance guard as the battalion moved through the small village of Kasteel towards Veghel. As Richard advanced down the road, people started coming out of their houses. They cheered and yelled, and held onto the paratroopers. By 4:30 PM on September 17, the 1st Battalion had captured their objectives and Company B was sent to the south-east of Veghel to hold the line. The only problem that occurred was that the Hollanders were still trying to stuff the American paratroopers with food and beer. I wonder if Richard smiled much on that day. I feel like he may have.

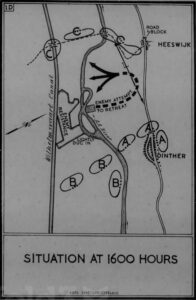

On September 20, 1944, with C Company in danger up near Heeswijk, the other two companies were moved in a sweeping motion to help relieve some of the pressure on C Company. Around noon, Company B met intense German fire and though the chaos caused some confusion, everyone held the line. The map that is titled “Situation at 1600 Hours” refers to the situation on September 20, 1944.

The next day, Richard was sent all through the streets in the surrounding area with his company, through light and dark but soon ended up running into German tanks, forcing them to pull back. They were surrounded…completely. At 10:00 AM on September 22, 1944, friendly tanks showed up to assist. If Richard was there, I bet he whooped and hollered. They were now going to push down towards St. Oedenrode with Company B in front. Sometime on September 22, 1944, Richard Charles Austin was killed by a mortar round fragment while leading a platoon. I have a feeling that he probably wasn’t killed right away. I’m not sure why I have that feeling, but I just do. Perhaps it’s because I don’t want to picture him lying there all alone, dead in the street. I’d rather believe that as he lay there bleeding out, one of the other men in his platoon had rushed forward and taken him in his arms, brushed the hair off of his face, and just told him everything was going to be okay. I guess I don’t want to think that he had been forgotten.

The boy from 180 Prescott Street, that beautiful boy– the one who left Norwich University to go join the ski troops, the one who should have graduated with the Class of 1944, he was gone. He should have made it. Did you know that he is one of I believe 5 men that were killed that day from Company B? He should have been here. If Private Richard Charles Austin were alive today, he would be 97 years old.