There was nothing special about December 7, 1941, to the Americans that woke up that morning. It was just a normal Sunday: get up, eat, get dressed, go to church, come home, prepare for work and school the next day. The people of Reading, Massachusetts woke up on December 7th to go about their business as usual, like every other town in America. Sleepy Reading boys and girls would roll out of bed at the yell of their parents, stumble down the stairs, eat, and get themselves dressed for another day of their lives. It wasn’t significant.

“Happy Birthday, John!” may have come the voices of John Calvin Penney’s parents, living on Gordon Road in North Reading, as they woke him up on his 17th birthday that Sunday in December.

Halfway across the world, in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii, the sun rose up the same way it did everywhere else, and all was calm…for now. John Russell Bird, a boy from 97 Franklin Street in Reading, was at that time a B-17 pilot stationed at Hickam Field, Hawaii. He had arrived very recently to serve as a flight instructor there. Francis John Thornton Jr., also known as Fran, from 74 Bancroft Avenue in town, woke up on December 7, 1941, aboard the USS San Francisco, docked immediately opposite and slightly behind Battleship Row, a section of water that would turn into a fiery pit of death within a few hours. Aboard the USS Pyro, also present at Pearl Harbor, was a young man named Arthur Francis Doucette, hailing from 100 Orange Street in Reading.

At 7:47 AM Hawaiian time, John Bird may have been sitting with his feet up, playing cards with his buddies. Perhaps they heard the drone of a group of aircrafts closing in on the airbase and thought nothing of it. Planes flew overhead all the time. Plus, a new shipment of B-17s were due soon, so it could just be them. As John’s turn to play his cards came, perhaps an explosion rang out in the distance. John may have looked up from his cards, eyebrows raised. Another explosion. Yelling. Screaming, even. Suddenly, the sounds of machine guns hitting pavement would reach John as the Japanese dive bombers strafed Hickam Field. Perhaps John slowly put down his cards and looked at the other men around him. They may have stared into each other’s eyes intensely until a very close explosion jolted them from their seats: a bomb had just come through the barracks and into the mess hall a few rooms away…during breakfast. And just like that, the men began to run.

There’s no telling which direction John may have run as all of this was happening. Perhaps he ran towards the mess hall, guided by the screams of his comrades, or perhaps he ran elsewhere in the building, to try to get others out. Maybe he did the smart thing and ran out of the building immediately, only to find that the outdoors was just as dangerous to him, with fires burning everywhere, bullets sailing through the air, searching for a fleshy target, and bombs falling. Regardless of whatever followed, it is a fact that Hickam Field would lose 121 men, have 274 more wounded, and 37 unaccounted for. John may have had some incredibly close calls on that day. Perhaps he carried a wounded man to an aid station; perhaps he helped pick up the rubble; perhaps he watched some of his friends die. There was no indication of what he had experienced in his communications home, though: all he said was that he was okay, and not to worry. What we do know is that John was there, and he saw it all, and he lived. But his life would never be the same.

Francis Thornton Jr., who was almost certainly aboard the USS San Francisco when the Japanese began to close in on Pearl Harbor and begin their bombing and strafing runs, may have been one of the many men who, at first, thought it was all a drill.

“Wow, they even painted the planes like another country’s planes!” Fran may have said, watching as the Japanese pilots motored overhead.

As their guns opened up on the men and ships in the harbor, Fran may have turned to the guy next to him and said, “This seems like a mistake–they’ve got live ammunition?” Perhaps, as soon as the words left his mouth, he realized just how odd the whole scene was. Suddenly, the dots may have connected for Fran and the sailors all around him: they were being attacked. The USS Arizona moored in Battleship Row was being lit up right before their eyes, and men were dying with every flash and bang as both dead and living bodies poured out of the ship. The USS Nevada was full of holes and on fire. The USS Oklahoma, whose hull was beginning to list heavily as she began to capsize, was currently being evacuated by her crew. As the men began jumping off and into the water, Japanese planes strafed the men right before the entire harbor’s weeping and burning eyes.

According to a letter that Arthur Doucette sent home, the men on the USS Pyro were very overwhelmed at first, knowing that all of their ammunition was below deck. However, he noted that once they got their munitions up and ready to go, that fear started to dissipate as the sound of gunfire rang in their ears.

General Quarters were sounded all across the harbor, but the crew of the USS San Francisco may have been confused as to what they were actually supposed to do because their ship was in Pearl Harbor to be overhauled, so her guns were not operational. Many of the men began trying to find ways to fight back. According to that same letter home from another Reading sailor, Arthur Doucette, Fran Thornton Jr. was seen by Arthur, shooting at an enemy plane. With that information, it is safe to assume that Fran was probably one of the many crewmembers of the USS San Francisco that went and augmented the gun crews of the USS New Orleans. Interestingly, in all of the Reading Chronicles that mention Fran, not once is there any mention of his experiences at Pearl Harbor. Perhaps it was an experience that was so full of trauma, and combat, and blood and gore, and acrid air, that he would rather forget about it.

Back in Reading, the people that did have radios were out on their porches and sidewalks, giving the news to the many people in town that did not have radios: “The Japs! They bombed Pearl Harbor!” All of a sudden, everyone in America was pulling out their world maps and trying desperately to find that little dot in the Pacific Ocean that was called Hawaii and then trace their finger to Pearl Harbor.

William Edward Friedlander, a 17-year-old man who lived with his family at 93 Washington Street in town, went and joined the United States Navy, no doubt in response to the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 16, 1941. A boy by the name of Linton Salmon, from 78 Charles Street, enlisted in the United States Army on December 15, 1941. Allen William Boyd, of 43 Line Road, would go and enlist in the United States Navy the day after Christmas that year. Herman Lawrence Marshall, a young man who lived at 48 Mill Street in Reading, went to sign up on December 31, 1941, ringing in the new year as a United States Army Air Corps member.

Although the draft had already been enacted back in 1940, it’s likely that American entrance into the Second World War would hit the young men of Reading, Massachusetts, with strength and power. Perhaps, it would hit them as they laid down to go to sleep that night, staring at the ceiling, wide-eyed, wondering if they would be one of the victims of war, the way the many unsuspecting sailors, Marines, soldiers, and civilians at Pearl Harbor had been. When John and Marion Doucette, the parents of Arthur Francis Doucette, heard the news about the bombing, their hearts probably dropped, knowing full well that their boy was there. For William Brown, who was a child living in Reading when Pearl Harbor was bombed, the news was barely noteworthy: “I went to play football with my pals that day, and my friend said to me, ‘Hey Bill, did you hear that the Japs bombed Pearl Harbor?’ I think I responded with something like, ‘Okay,’ and we kept on playing.”

All heroes have origin stories. This is the origin story, the keys in the ignition, for an entire generation of Reading men and women: the attack on Pearl Harbor, December 7, 1941.

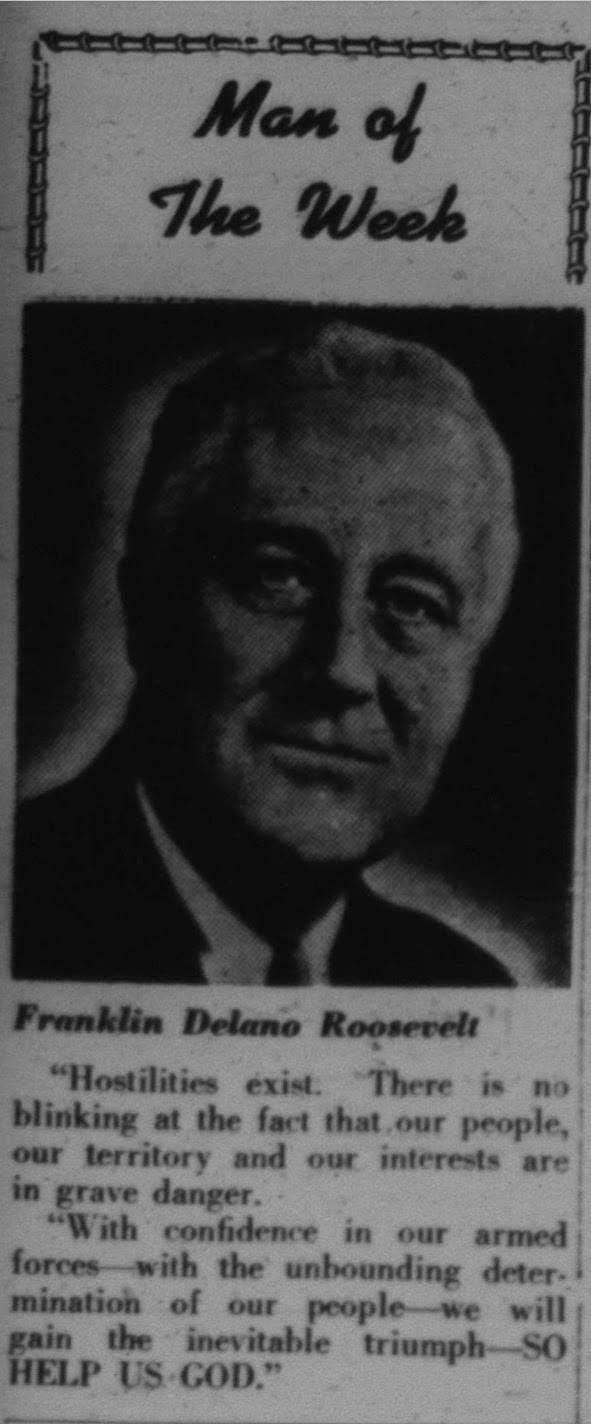

Photo from the Reading Chronicle, December 12, 1941.