There has to be a solid reason why there are eighty cities, towns, and counties in America, including seven streets in Boston and one in Reading named for a visitor from France. It is fitting that America has shown its love and respect for its hero, the Marquis de Lafayette. Lafayette visited Massachusetts on eight different occasions: six during the revolution and in 1824 and 1825. In February of 1824, President James Monroe, following a joint resolution from Congress, sent a long-overdue invitation to Lafayette to visit America. The letter expressed the “sincere attachment of the whole Nation whose ardent desire is once more to see you amongst them.” Lafayette departed France on July 13, 1824. He was accompanied by his son, George Washington Motier de Lafayette, as well as his secretary, Auguste Levasseur. Throughout the journey, Levasseur documented Lafayette’s travels while recording fascinating observations of life in the United States.

During his 13 months in America, Lafayette visited all the states at the time, including two separate visits to New England. During the visits, Levasseur kept a concise journal with a daily schedule along with comments concerning American history, society, and politics. His book, the source for many quotes in this piece, Lafayette In America or Journal of a Voyage To The United States, is a fascinating read as it is an observation of America and Americans by an educated European. Our Reading library has access to a copy of his journal through the library’s NOBLE district lending service.

This article will concern Lafayette’s two visits to the Boston area with all the excitement that followed as the whole area continued to turn out to honor its Nation’s Guest. No matter where he went, he was treated as a hero, being the last surviving American Revolutionary general. He arrived in Boston on August 24, 1824, and on the next morning; there was a grand procession to Boston. “In front of the State House, upon an immense terrace, whence the sea may be discovered, was a long double row of girls and boys, from the public schools all decorated with Lafayette badges, uttering cries of joy?”

The entourage entered the State House chambers of the House of Representatives and Senate where “all the public functionaries were gathered.” Here Lafayette recognized his old military friend, and former Governor of the state, John Brooks. Brooks was the Reading town doctor who led the Reading Minutemen to Concord on April 19, 1775. Brooks was the hero at the Battle of Saratoga, and aide to George Washington and Lafayette at Valley Forge. Lafayette reached out to his old friend John. “At first sight, he embraced with great cordiality and affection”. After the festivities, the group left the State House, passed under Charles Bulfinch’s Triumphal Arch, and retired to the Marlborough Hotel for a respite.

Here, Lafayette met with Madam Hancock (widow of John.) Madam, along with many Boston women, were wearing Lafayette gloves. Louisa May Alcott, in her The Jones 1st-5th Reader, describes the meeting: “Lafayette bowed first to the Governor’s widow and kissed her hand… That was droll; for on the back of her glove was stamped Lafayette’s likeness, and the gallant old gentleman kissed his own face.”

In the evening, the entourage dined with Governor Eustis at the Exchange Coffee house, where many toasts were offered. The French and American flags waved united: “A toast to the memory of Louis XVI, none of the friends of liberty should be forgotten although they might have worn a crown.”

On the 25th, Lafayette attended the commencement at Harvard College. Levasseur noted that the splendor of the ceremony “was considerably increased by the presence of a great number of ladies, attracted by the desire of seeing Lafayette.” Levasseur described Cambridge as “one of the richest and most beautiful villages in New England.” He complimented Harvard by noting: “The citizens of Massachusetts are proud of its success and support it with a liberty which proves how much knowledge and education are esteemed in this state.” However, Levasseur was not above criticizing much of the hypocrisy he saw in Massachusetts and America. For example, he noticed that the Massachusetts constitution barred non-Christians from holding political office at that time. “We can scarcely comprehend how, in a society so free and enlightened, where the progress of philosophy is every day evident, the state still can continue to refuse the services of a virtuous man because the individual may be a Jew or a Muslim.”

On August 27, Lafayette visited Bunker Hill, along with John Brooks, where they inspected the base of the later-to-be-built monument. Levasseur mentions that “Bunker Hill reminds all of the noble struggles of liberty against tyranny and oppression. It was at Bunker Hill that the Americans first dared in a regular fight to brave the arms of their tyrants.”

Lafayette had maintained a strong friendship with John Adams and refused to leave Boston without visiting his old friend. On August 29, he set out for Quincy. The first thing Levasseur noticed was the simplicity of the Adams residence: “Our carriages stopped at the door of a very simple small house, built of wood and brick, and but one story high. I was somewhat astonished to learn that this was the residence of an ex-president of the United States… During the whole of dinner time, he kept up the conversation with an ease and readiness of memory, which made us forget his 89 years.” Adams was so pleased to hear about the gratitude of his fellow citizens towards Lafayette. The next day, Lafayette left to visit other states.

After nine months visiting throughout America, Lafayette returned to Boston on June 15, 1825. His return was met with sadness as Lafayette learned that his two good friends, Governors Brooks and Eustis, had passed during his absence. Levasseur commented that these two companions had “seen our old general. We have lived long enough”. Lafayette was received at the State House where Governor Lincoln, the senate, house of representatives, and civil authorities “rose and in the name of the State of Massachusetts and congratulated the Guest of the Nation on the termination of his long journey.”

According to Levasseur, “The sun of the fiftieth anniversary of the battle of Bunker Hill rose in full radiance.” At 10:00, 2000 free Masons, sixteen companies of volunteer infantry, and a corps of cavalry assembled in front of the State House and marched to escort General Lafayette. The procession, numbering over 7000, proceeded “to the sound of music and bells, in the midst of 200,000 citizens, collected from all states of the union. At the site of the monument, invited guests were seated. The survivors of Bunker Hill formed a small group and before them, in a chair, was the only surviving general of the Revolution. Being a Grand Master of the Masonic order, General Lafayette was called upon to lay the cornerstone of the monument. After Daniel Webster’s oration, a banquet was held at the site. Lafayette rose to thank those for erecting the monument and concluded by offering a toast. “Bunker Hill is the holy resistance to oppression, which has already disenthralled the American hemisphere, and the anniversary toast at the jubilee of the next half-century will be to Europe, freed.”

Lafayette remained a few more days in Boston, which included one last visit to John Adams. On his way to New Hampshire and Maine, he stopped by his old friend Governor Brooks’ and our hometown of Reading and was treated to a celebratory luncheon at Skinner’s Tavern.

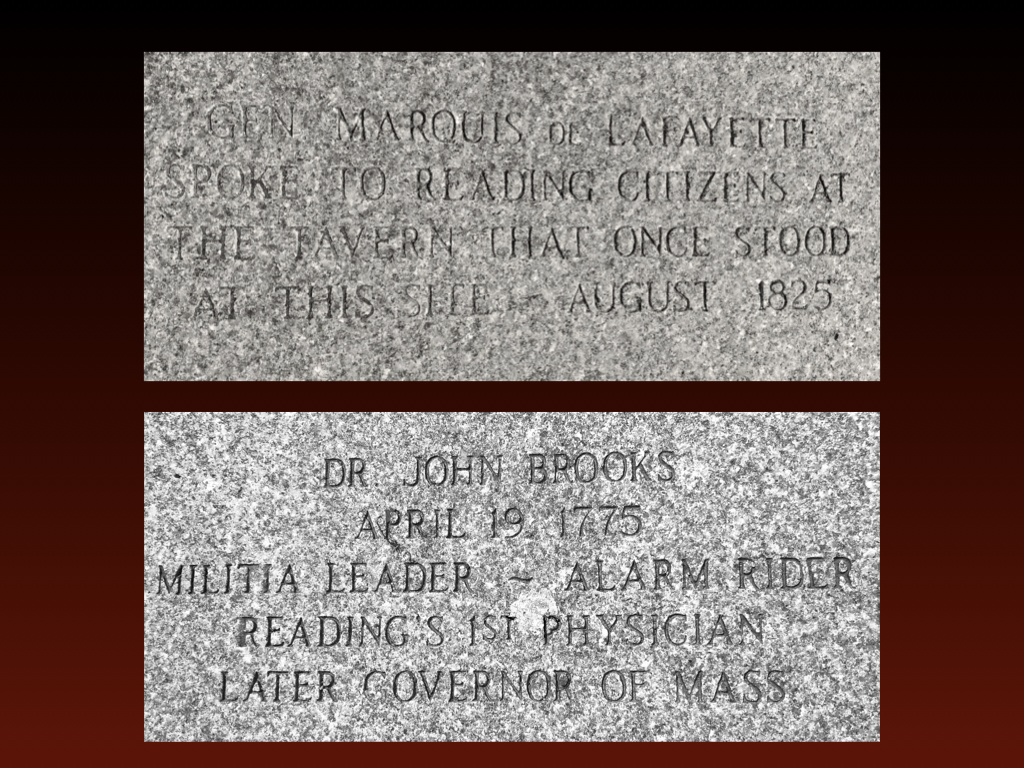

It is satisfying to note that the town of Reading has acknowledged the greatness of John Brooks and General Lafayette with granite sidewalk markers on either side of Main Street in the square. The markers are positioned fairly opposite each other. Some may say our heroes are back together again. Or, some might suppose Main Street to be the Atlantic Ocean separating our two heroes in their honored resting places.

The General left Reading and America for a final time with vivid memories of the population’s appreciation for his service during America’s quest for freedom.