For those of you who do not know me, my name is Autumn Hendrickson. I graduated from Reading Memorial High School with the class of 2020. For the last three years, I have been working on a book about the men and women from Reading and North Reading that served in World War II. I would like to take this time to tell you all about the story of two individuals from the town of Reading, Massachusetts, killed in action in World War II, and what we can all learn from their deaths.

Memorial Day 2023 – Laurel Hill Cemetery

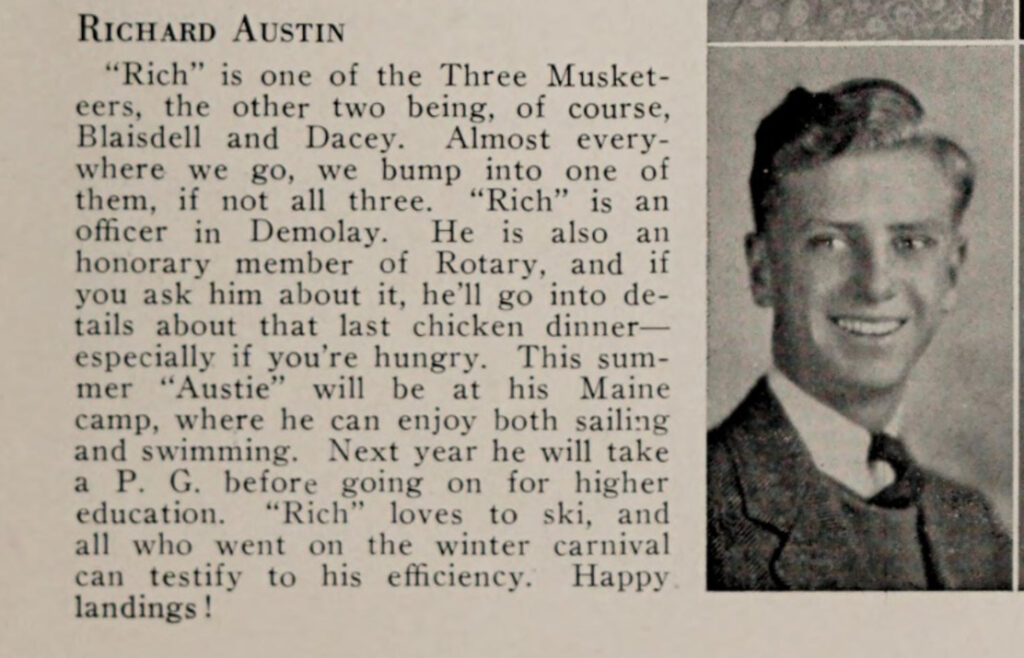

Richard Austin

I would like to take the time that I have been allotted to speak today to briefly tell you the story of a young man from Reading who was killed in the Second World War, and whose remains lie in this very cemetery.

Richard Charles Austin was born in this town to Irving and Thelma Austin on October 13, 1922. He was their first child, and spent his boyhood on Prescott Street in Reading. Graduating from Reading High School with the class of 1939, Richard then went to Vermont Academy for a postgraduate year before finally deciding to pursue a college education at Norwich University, a private military college, in Northfield, VT. After the outbreak of the Second World War, and America’s entry into it, the federal government ordered that all Norwich cadets be inducted into the United States Army, and in March 1943, Richard answered his country’s call unquestioningly.

After serving with the 10th Mountain Division (the ski-troopers) in Colorado, Richard then volunteered to be transferred to the Airborne. Richard would jump into Normandy on D-Day as one of those brave paratroopers, before being pulled back to England for some much-needed rest. The next time the 101st Airborne Division was called into action was in September 1944 for Operation Market Garden, a coordinated paradrop into Holland. Alongside the British Airborne and the 82nd Airborne Division, Richard jumped from an aircraft into Holland with his unit on September 17, 1944. After being welcomed joyously by the Dutch people there, Richard’s unit moved quickly into battle, and on September 22, 1944, in the vicinity of Schijndel, Richard’s life would be cut short by a mortar round that would strike him in the shoulder.

At the time of his death, Richard had on him $3.77, which would be mailed to his mother and father in the form of a check on June 9, 1945. He also had on him 1 unmailed letter to a friend in Arlington, Massachusetts and an addressed envelope to his father. He had also kept some of his parachute’s silk, perhaps because he hoped, like so many other paratroopers, to be able to send it home to his girlfriend of 2 years, Jean MacIntosh, back in Colorado where he had trained with the 10th Mountain Division, for a wedding dress… When his death was reported in the Reading Chronicle on October 13, 1944, which would have been Richard’s birthday, the article remarks, “Hope is still held by the family that the report is in error.” Of course, it was not.

The people of Reading joined the Austin family in the mourning of their deceased son, though, and did so in such a way that it was remarked in the newspaper on January 12, 1945, that the “Unitarian Community Church was filled to capacity last Sunday afternoon for the memorial service for Richard Austin…” During that time, Richard’s grave, which was then located all the way over in Holland in an American Military Cemetery now known as Margraten, was being cared for by a man named Ben Greve, who wrote to the Austin family to inform them that he would watch over Richard’s remains.

On January 6, 1949, at the request of his parents, the remains of Richard Charles Austin arrived in Reading on the 5:00 PM train, guarded by a young soldier. Shortly thereafter, he would be permanently laid to rest in Laurel Hill Cemetery. If you walk over the hill and to the left, and go all the way to the Highland Street entrance to this cemetery, off in that little corner, you will find the headstone of the Austin family. To the front of the stone, you will find a placard in the ground with the words, “Richard C Austin, Massachusetts, PVT, 501st Parachute Infantry Regiment, 101st Airborne Division, October 13, 1922-September 22, 1944.” Six feet beneath that placard lies the remains of one of Reading’s great heroes, and one little boy who grew up at 180 Prescott Street.

Memorial Day 2023 – Charles Lawn Cemetery

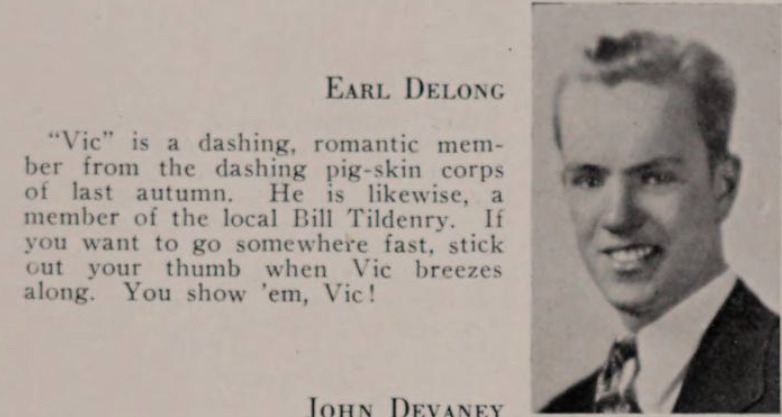

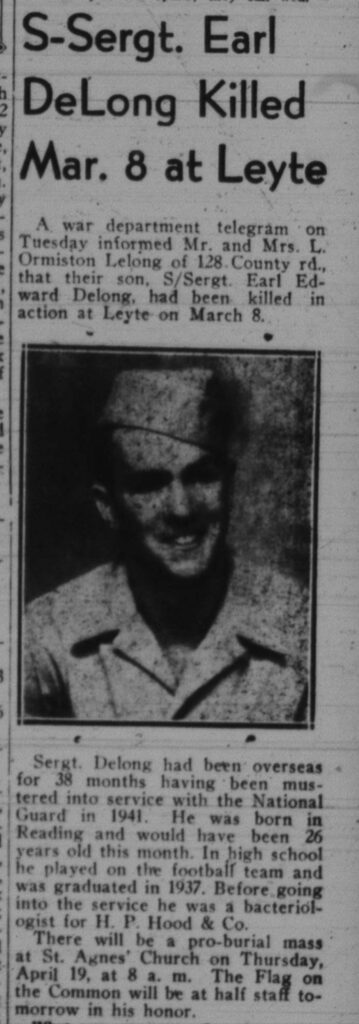

Earl DeLong

Earl Edward DeLong was born on April 26, 1918, to Ormiston and Marion DeLong, both immigrants to this country. Earl was one of 4 children, and spent almost the entirety of his life on County Road in Reading. While attending Reading High School, Earl played on the football team for two years before his graduation with the class of 1937. Earl, like so many other Reading men, was drafted into the United States Army in February 1941 and assigned to the 182nd Infantry Regiment, an original regiment of the 26th “Yankee” Infantry Division, Massachusetts’s National Guard Division. At the outbreak of war with Japan, the United States realized quite quickly the incredible lack of manpower either deployed or designated for the Pacific Theater of war and decided to send the 182nd Infantry Regiment to the Pacific with haste. So, alongside many of his neighbors and friends, he shipped out of the United States from New York in 1942.

In the late fall and early winter of 1942, Earl DeLong would join the fighting on Guadalcanal with the rest of the 182nd Infantry Regiment. He would fight on the island of Bougainville, as well, where he would earn a Bronze Star. The citation for the Bronze Star was published in the January 19, 1945 issue of the Reading Chronicle, and it read, “Sgt. DeLong, a platoon guide, was advancing with a rifle squad toward stubbornly entrenched Japanese pill boxes that occupied the ridge of a hill, when he saw one of his men fall wounded. Although the wounded man was within grenade range of the Japs, DeLong crawled forward up the steep uncovered slope and successfully dragged the soldier to a place of safety.” After the fighting on Bougainville came to a close, it would seem that almost every single Reading man serving with the 182nd Infantry Regiment would be rotated home and reassigned to stateside service, not having to enter combat ever again. Except for Earl Edward DeLong of 128 County Road. It is most likely that Earl was not rotated home simply because he asked not to be, preferring to stay, for whatever reason, with his unit.

In January 1945, the 182nd Infantry Regiment of the Americal Division, now filled to the brim with replacements who had perhaps never seen combat before, and were most certainly not all from the same general area north of Boston, Massachusetts, landed in the Philippine Islands to assist in the so-called “mop-up” operations in Leyte. For the next few months, Earl’s combat experience and guidance would help usher in the many green troops under his command as an NCO. Finally, as the 1st week of March began turning into the 2nd week of March, the operations of the 182nd Infantry Regiment were winding down. However, somehow, on March 8, 1945, Earl DeLong’s luck finally ran out. The June 29, 1945 issue of the Reading Chronicle told the story of Earl’s last moments when it printed the citation for the Silver Star Earl would receive posthumously: “Acting as a platoon sergeant, DeLong was confronted with a strong [Japanese] position from which heavy, accurate fire was being laid on the platoon. Despite perfect Japanese observation, DeLong led his platoon in a strong assault on the position, personally accounting for three enemy dead. In the firefight which ensued, Sergeant DeLong was killed by an enemy sniper at close range.”

To me, there is something about DeLong’s death that stands apart from the rest of Reading’s World War II dead. For a time, I could not quite identify what it was, but I now believe it has something to do with what I can best describe as a warrior’s death. Sergeant DeLong was with the 182nd Infantry Regiment from the very beginning of its time in combat. He rose from being the same green, inexperienced soldier that every other man around him was when they landed on Guadalcanal to being a platoon guide on Bougainville, and then, to a platoon sergeant on Leyte. He was not forced to go and fight in the same way that so many others were. He did not have to stay with his unit after Bougainville; he easily could have chosen to go home. But some part of his brain had decided that this was where he belonged, and this was where he wanted to be, and this was where he was going to do his part. That was undoubtedly a personal decision, just as it was for all of the men who decided to return home. Earl DeLong knew what combat was like, he had seen friends and enemies bleed and die, and he knew what it took to lead.

When dawn came on March 8, 1945, Earl DeLong knew exactly what he had to do, and he did it the only way he could: by demonstration. Encouraging his men to close the distance between themselves and the enemy, Earl did the same himself. He was not picked off by an unseen sniper a mile away, and he did not fall in the no-man’s-land between himself and his destination, no. He met the enemy at an arm’s length. The Japanese sniper who killed him was probably just as surprised to find an enemy infantryman feet in front of him as Earl was to have surprised him. There was no time for thought, it was simply a matter of who fired first, and that time, it was the Japanese sniper. A warrior’s death is ideally going to be quick, painless, and proud. Earl’s might have been quick, might have been painless, and might have been proud, but it was far too soon and too far from home. He likely knew that he could die, but he was no longer a soldier. He was a warrior because he decided to be. He knew that if he died on that hill but his men took it, that that was just a part of war, and he knew that he would have done his part. It is a complicated thing, to be a warrior. In some ways, it means to be so intent on doing your duty as a soldier, that you forget your very own humanity. But at the same time, it is a choice made by an individual with the free-will to do so, and in many other ways, that is, perhaps, the height of humanity. Very few individuals have it within themselves to become that warrior, but Earl did. I like to think that he died on that hill because he did the math out in his head and chose to.

Very often, on Memorial Day, we can get caught up in the reverence of the hero or warrior’s death. Heck, I just spent the last 5 minutes telling you about one. But I shared this story with you not to elevate it above any other, but to distinguish between it and others. This day, and everyone after it, I hope that all of us can do our best to remember the difference between the death we choose and the death we get. For so many war dead, the death they get is a far cry from the one they would have chosen for themselves. Memorial Day is as much for them as it is for deaths like Earl’s. Memorial Day is for all of those crosses and white stones whose names we do not know, but whose patriotism we do, because they represent an idea far greater than ourselves.