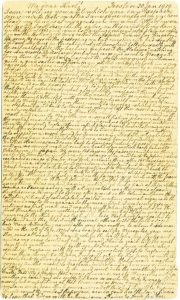

You often hear the phrase “six degrees of separation,” well, maybe not so much. When I was growing up, my grandmother would talk about her father, Ernest Kersten, a sea captain. We were lucky to have the history of his life at sea, written in his own hand when he was in his early 70’s, on a 3×5 postcard.

The handwriting is very small and requires a magnifying glass to read it. About 50 years ago, I began to work on my family genealogy, and of course, out came the postcard from safekeeping to learn more about him. The details included each ship he sailed on, which ports they sailed to, the cargo they carried, and even the details of a typhoon en route to the Philippines from China and a shipwreck off the tip of Cape Breton. His journey began in the fall of 1862 when at the age of about 14, he traveled from his home in Dresden, Germany, to Hamburg and signed on as a cabin boy on a brig called the Superb bound for Singapore. One hundred sixty-five days later, they arrived.

He wrote, “inside the harbor, we passed the Alabama, watching for Am. Vessels.” This was the age of sail. Every harbor would be crowded with hundreds of ships. Why did he mention the Alabama specifically? My memories from high school history classes failed me. But it wasn’t hard to find out that the Alabama was secretly built in 1862 in Liverpool, England, for the Confederate Navy. It spent the next two years sailing the world looking for Union ships. She sank or captured 66 vessels and took 2,000 prisoners.

By the way, my great-grandfather spent the next 20 years sailing the world and working his way through the examinations to reach the rank of Master (Captain). He even had a ship built in St. John, New Brunswick, named after my great-grandmother, the Mary A. Kersten.

Fast forward to the celebrations of the 150th anniversary (2011-2015) of the Civil War and my interest in Reading’s Civil War soldiers and sailors. According to Eaton’s history of Reading, published in 1874, 411 people were credited with serving “from or for” Reading during the Great Rebellion. There are so many fascinating stories. One of those that connected with me was that of Sydney Smith. He was born in Boston in 1838. The 1855 Massachusetts census shows that he was living with his parents and four siblings on Temple Street. He graduated from Dartmouth College and enlisted in the Navy in October of 1861. After the War, in 1870, he lived in Reading with his grandmother, Polly Parker Smith, whose house was located where the Paint Store with the Purple Door and Anton’s Cleaners is now on Harnden Street.

But it is his service in the Navy that caught my attention. He was an officer aboard the U.S.S. Kearsarge. That name may not be familiar to you, nor was it to me, which prompted a little more research. The Kearsarge was the ship that engaged the C.S.S. Alabama in battle off the coast of Cherbourg, France, on June 19, 1864. After little more than an hour, the Alabama began to sink. Many of its sailors were rescued, the captain and 41 crew members were picked up by a British yacht and escaped to England, thus avoiding prosecution.

After the War, he reenlisted in the Navy and served until 1880, and lived in Roxbury at the time of his death in 1914. He was the last surviving officer of the Kearsarge and is buried in the family lot at Laurel Hill Cemetery. His name is inscribed on the obelisk in that lot.

Three degrees of separation? Maybe not; read on.

A little over a week ago, we went to the GAR Post No. 5 building in Lynn. The GAR (Grand Army of the Republic) members were all Civil War soldiers or sailors. It was a precursor to the American Legion and the Veterans of Foreign Wars. We had heard the building itself was remarkable (it is definitely worth a visit), included many artifacts from the Civil War, and had photographs of most of its members. I was hoping to find the photographs of four Reading boys who belonged to that Post after the War. And indeed, they did have them.

While there, we noticed a display about the Kearsarge – there were several photographs, including one with Sydney Smith and a model of the Alabama. And there, in the middle of the room, was the capstan from the Kearsarge. Crew members used a capstan to help put up the sails on a vessel. The story that we were told was that the Kearsarge was in Boston for repairs. When the repairs were finished, the capstan was missing! Hmmm.

The fascinating thing about genealogy and history is the connections that it uncovers.