Introduction

Those of you who know about the Second World War know what this issue is going to be about. I need not tell you. But those of you who may be less familiar with the war may only recognize the name: the Battle of the Bulge. The battle that took Christmas from the cold, dead hands of so many American boys. As the Allied powers would soon learn, the German Army was not even close to the horrible state we believed it to be in. Just as Kaiserschlacht was the last great German offensive of World War I, Operation Autumn Mist would be the last great German offensive of World War II.

Close your eyes for me. Clear your mind for a few moments. I want to take you on a journey. We will be leaving Reading this time. Imagine that you are standing in the middle of a forest. There is not a lot of brush– it is mostly flat ground and trees. The trees are too thick for you to lock your left hand into your right one if you hugged one. The trees are evergreen, and they shoot up toward the sky to form a neverending canopy. It is dark around you. You take a step forward, and something crunches beneath your foot. It is snow. Suddenly, you begin to realize how cold it is. You have no gloves and no coat, just the button-down shirt you came herein, your pants, and your boots. The silence is eerie. You almost expect one of the trees to begin talking. Living in Massachusetts, you know how the snow makes everything quiet. But that was peaceful, and this is not. You cannot hear anything other than silence, and it fills your mind. You see a man approaching you in the forest. He has on that distinct German helmet, you can tell. You want to run, but something keeps you rooted to your spot. He is shivering violently, and his hands look blue.

“Bitte,” he whispers to you, standing about five feet ahead of you before he crumples to the ground. Your eyes probably widen. You are scared. He looks scared. You are haunted by the look in his eyes. He is dying. Now open your eyes again and look around. Does the Battle of the Bulge feel a bit more real to you now? Do you feel cold? Did you wish you could have helped that poor German soldier, as life left his body?

I’d like to tell you that if you did what I asked, and you closed your eyes and tried to imagine the scene I painted for you, then you, for a moment, had stepped into the shoes of one of your Reading boys during the Battle of the Bulge, and for that matter, the shoes of many others. After all, that winter was the coldest winter the Ardennes region had seen in 50 years.

Into the Forest

If you were a bird flying over the Ardennes Forest during the winter of 1944-45, all you would probably see was snow. From east to west, it would just be snow. The wind would ruffle your feathers and sting your eyes. But we are not birds. We are humans, and we walk through the snow rather than fly over it. So you and I will have to bear the elements the way they did – the way Reading’s boys did.

For John Austin Cahill, of Everett and later Reading, the early days of December 1944 spoke for themselves. As the 423rd Infantry Regiment, 106th Infantry Division moved up through the lines after having landed in France, the weather began to freeze over, the snow falling first gently and then faster. The road conditions started to deteriorate. A policy of radio silence made controlling the column of transports almost impossible. But still, it was beautiful. The landscape may have reminded John of home, of the way the snow would pile out in his backyard, and how his parents might ask him to wake early to go shovel the walkways. And then he’d see the burnt-out skeleton of a tank and remember he wasn’t in Everett anymore.

The 106th Infantry Division had never seen combat before. They had been placed in the Ardennes Sector because it was known as a quiet sector. Only light patrolling had taken place there for the past few months, and the idea was that putting the green troops here would let them get their feet wet at their own pace. So, there John was, in St. Vith, Belgium: A place whose name would likely become imprinted in his mind for the rest of his life and would always bring back memories of a frigid struggle for survival. A place whose streets his friends died in. A place where any small piece of hope floated away like lint in a breeze: only the lucky could trap the piece in their hands. It was a place where good men went to die.

To the south, Harry Lincoln Beeth and Howard Albert Mason were heading into combat as well. Though I am not completely sure that Howard was with the 12th Armored Division during the winter of 1944-45, I have been working off the assumption that Howard probably joined the 66th Armored Infantry Battalion, 12th Armored Division sometime in January or February 1945 as a replacement.

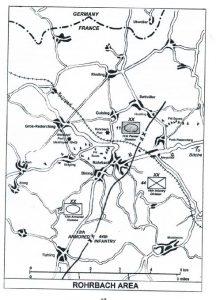

On December 9, after having relieved another armored division in the vicinity of Bining, the 23rd Tank Battalion, of which Harry Beeth was a member, was sent into action. Harry, a native of Syosset, New York, would only spend the closing years of his life in Reading, but much like Joseph Keenan, I have concluded that Harry is, indeed, a Reading boy. A tank from Company A of the 23rd Tank Battalion was sent into a nearby German barracks with a small number of infantry from the 17th Armored Infantry Battalion. At the same time, Harry and the rest of the battalion sat back, firing on the barracks from a flank.

As the Company A tank rolled up the snowy hill, Harry, a tank commander who would have sat up in the open hatch watching the surroundings, probably would have cringed as he watched the tank hit a cluster of anti-tank mines. The infantry around the tank probably would have thrown themselves down into the snow to avoid any stray shrapnel. After years of training for combat, here they finally were. Blood probably covered the snow in places.

As the sun fell that day, the world began to grow even colder. I wonder if Harry or Howard looked up into the night sky that night and just stared at the stars, or if it was too cloudy to see them. I wonder if they were awed by the quietness of the world when the snow falls, the way I am still awed. That night two men from Harry’s Company B left on a jeep to go pick something up, and as they returned to the Command Post (CP), they hit a landmine. One of the men was killed and the other seriously wounded. I imagine it woke up the entire battalion.

On the morning of December 11, after having their attack repeatedly thrown back, Harry’s 23rd Tank Battalion again began trying to move up. When the Germans heard the squeaking of the American tank tracks, the 23rd Tank Battalion was met by the most intense bombardment it had ever experienced. Men were quite literally blowing up all around Harry Beeth.

As for Howard, I do not know much about his actions during this period (or if he was even in Europe with the 12th Armored Division yet), but I can imagine that he shared some of the same fear and anxiety that Harry Beeth probably felt. They were heading into the Forest of Death, whether they knew it or not.

For Joseph Warren Keenan, of Company L, 329th Infantry Regiment, 83rd Infantry Division, the mission that he had had in the months before December hadn’t changed much: the men of his unit were still patrolling the Sauer-Moselle River line vigorously. On December 9, that would finally change, though. The 329th Infantry Regiment was being moved to the vicinity of Gressenich, Germany. They were going on the offensive.

On December 13, 1944, at 8:30 AM, Joseph Keenan’s L Company would move through the woods around Gressenich and meet little to no resistance but struggle to move in unison due to the dense forest. Nonetheless, their objectives were achieved, and because of their success, the unit was asked to move up yet again, to take the town of Birgel, which was surrounded by woods and then a 500-yard clearing before entering the town. The attack was a complete success, with the 3rd Battalion (Joseph’s battalion) taking minimal casualties and walking down the main road of Birgel within 20 minutes. The men of the 329th Infantry Regiment were no longer in the woods but in the open fields. On December 15, 1944, Joseph Keenan would be given command of Company L. Our Reading boy was going to lead a group of very brave young men in the days still to come.