On October 16, 1940, a young man by the name of Edward Palmer walked into the town hall in Stoneham to fill out his draft card. Although Edward didn’t grow up here in Reading but grew up in Stoneham, just a stone’s throw away, Edward would come and settle his family here in Reading after the war had ended. I am writing this special issue about Edward because, in April 1943, Edward was transferred to the US Navy School of Photography in Pensacola, Florida, and would remain there for the duration of the war. As some of you may know, my series started with June and July 1943 so Edward’s overseas experiences had already passed by then…and boy, did he have a few stories to tell.

Born on September 24, 1917, Edward Palmer was 24 years old when he entered the Navy on February 13, 1942. Edward would complete his training after entering the service and would be assigned to one of the US’s battleships: the USS Massachusetts. As Edward would soon discover, the USS Massachusetts had been assigned to support the landings in North Africa during the later months of 1942. Starting on October 24, 1942, Edward Palmer began keeping a log of the goings-on onboard the Massachusetts. Though this was against US Navy policy, it was not an uncommon thing for men to do, and because of this log, myself and many others have the fortune of having a first-hand account of the Naval Battle of Casablanca.

The first entry in Edward’s log seems to be tinged with pessimism and concern. Though Edward is good about masking this emotion by including typical information that one might find in a ship log, it still comes through: “Sea is calm and a full moon shining brightly. Not too cold either. Sailing in a southeasterly direction. We also have a War correspondent with us – looks bad…” It leads me to believe that Edward composed those four sentences while standing on the top deck, watching the sunset and the moon rise in its place like he took time to reflect on the symbolism of it all in those moments. In the entries that Edward makes following his first October 24, 1942 entry, he mentions multiple times how awed he is by the apparent size of the operation he is participating in. It makes me smile a little bit, picturing this young man dressed in his Navy uniform with his eyes wide and a grin spreading across his face, just appreciating the overwhelming emotional and physical power of a military that functions in unison.

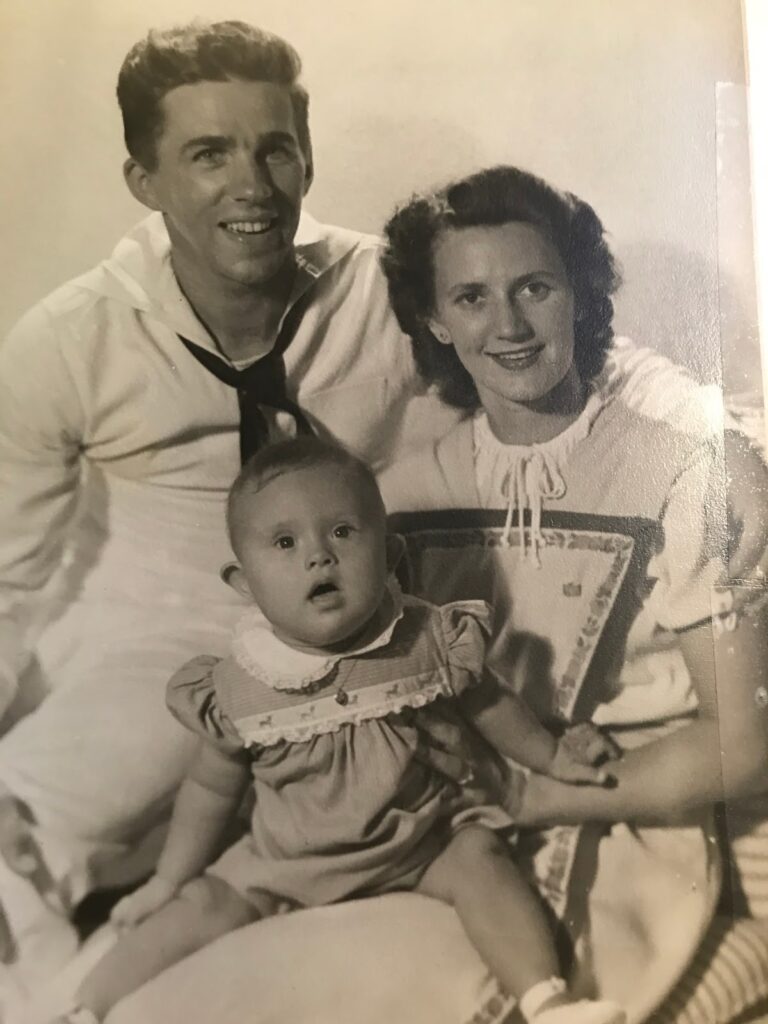

In an entry on October 28, 1942, the same day that Edward finds out the Germans are sending ships of their own to meet the USS Massachusetts and her task force, Edward took time to go out on the top deck with his buddy to watch the battleship proceed through squalls of rain and remarked on the beauty of the rainbows and talked about his wife-to-be. He closed the entry with the sentence, “Still hard to believe we are really in a War…” Every time I think I understand the magnitude of the bravery of some of these men, I find something that humbles me again. This is one of those things. Edward Wallace Palmer, who in a few years time would make his home at 45 Pratt Street, Reading, Massachusetts, is well aware of the enemy’s presence in the area but is able to find it within himself to put it out of his mind for a time to simply live his life.

As though the sea knew what the USS Massachusetts was heading into, she began to rock and roll the hull of the elegant battleship that Edward called home in the days following October 28, 1942. Almost as if to say, “Are you sure you want to continue?” In the evening, Edward expressed the same thought that I am certain many Reading boys, and boys from all over the world felt: he wondered aloud in his log if his girl was looking up at the moon as he was.

On November 1, 1942, I got my first glimpse of Edward Palmer’s clear maturity for such a young man: “Everyone speaking of their return to Boston as a natural event without any doubt that it might never happen.” I have found this maturity to be a relatively common characteristic for these men, but I don’t think I have seen any other Reading boy be so frank and blunt about the reality of the situation facing them until right here.

One evening, after confession had finished and the Chaplain that Edward worked with was too tired to continue, a man came up to Edward (who was about to explain to him that confession was over) and began to unload all his feelings on Edward. The man told Edward how a few years back, he had been driving his girlfriend home when he crashed the car. His girlfriend was killed in the crash, and the young man was so terrified about facing her parents and his own that he left and joined the Navy. The man began to cry and Edward was not sure what he was supposed to say. When he finally found words to comfort the other sailor, it was nearly 1:00 AM, and Edward remarked in his log that it now made a lot more sense why the Chaplain seemed so tired all the time. Just this one painful confession from this man weighed Edward down more than he had imagined was possible.

In the early hours of November 8, 1942, Edward began to notice splashes of water near the hull of the battleship and it finally hit him: they were being fired upon. Edward immediately dashed to his telephone to keep communications up, but the concussion from the Massachusetts’ 16” guns completely killed the telephone’s connection and he had to run-up to the conning tower to hook up there. The guns belonging to “Big Mamie,” as the sailors called the battleship, continued firing back at the enemy when an explosion shook the front left side of the ship. They had been hit. And still, more bad news: three torpedoes were called out by the watchmen and they were heading right for the left side bow of the boat. An order to turn the rudder all the way to the left was given, and the ship shook and jolted from front to back but completed the turn and just like that, the torpedoes passed five feet in front of the massive ship. That day, the USS Massachusetts would throw an enemy battleship called the Jean Bart out of action and unable to return fire while also taking out a small number of other enemy craft. Edward Palmer was pleasantly surprised by Massachusetts’ good fortune. Edward and the crew of the USS Massachusetts would return to the states but I do not believe he got the shore leave he so desired.

In February 1943, Edward would sail on the USS Massachusetts for the last time before leaving the ship in April and would of course end up going through a massive storm while he was on board. He remarked that he was pretty sure just about everyone on board the ship was seasick for a week or so. On February 11, 1943, Edward Wallace Palmer unknowingly witnessed a US aircraft carrier that did not yet exist. While entering the breakwater in the Panama Canal Zone, he and the rest of the crew of the USS Massachusetts noticed a British aircraft carrier called the HMS Victorious being refitted with American planes. In early 1943, when our men began making landings in the Pacific, we started to realize that having an aircraft carrier to cover the landings was essential, but there was a problem. We didn’t have any because all of ours were either undergoing repairs or severely damaged. So the British leant us one of their aircraft carriers, and her British crew was issued American uniforms and American planes, and the HMS Victorious was temporarily renamed the USS Robin.

The next few months would pass without much excitement until Edward finally found out that his transfer to the US Navy School of Photography had finally gone through in March 1943. He would leave the USS Massachusetts not long after hearing the good news and he would begin making his way back to the states aboard a British ship.

Edward graduated from the US Navy School of Photography in Pensacola in September 1943 as a Photographer’s Mate 2nd Class and was appointed an instructor of photography, serving until September 1945. After the war ended, he returned home and worked many different jobs, many of them in the technological sector. Sometime after his return home, Edward moved to Reading and made his home at 45 Pratt Street.

Many people who have served in the military remark after they retire that their time in the service changed them on a fundamental level. Something about serving in the military can change you. The way you think can change, the way you view the world can change, the way you experience things can change, just about every moldable part of a human’s character can change through military service. In this way, it is not unlike the changes that we go through when we attend school or college. I like to think that whenever we leave behind a place that changed us in some way, we leave a little piece of ourselves there. It is a part of our origin story, regardless of where we end up. In some way or another, it made us who we are. Well, in 1962, the USS Massachusetts, a ship on which many lives were changed, for better or worse, was about to be struck from the Navy Register of Ships and scrapped.

On some random morning in early 1963, a newspaper clipping caught the eye of our Edward Palmer: oil was being pumped out of the USS Massachusetts in preparation for her eventual scrapping. With the focus and dedication of a man on a mission, Edward gathered together two former crew members and they met for lunch. They needed to save their battleship. After contacting the Navy to find out what needed to be done to save the ship, Edward and the two other men (Frank Letourneau and Jack Hayes) went to see the governor of Massachusetts. When they spoke to Governor Endicott Peabody about the formation of a State Commission to save Big Mamie, as she was affectionately referred to, the governor replied with a quick, “No.” The men stood their ground, though, and requested that the governor send a telegram to the Navy to delay the scrapping of the battleship so that the men could get together enough funds to save the ship themselves. The governor obliged but remarked that he doubted they would be able to save the ship. The effort to save Big Mamie was now in full swing, and bumper stickers were being sold, articles published, and politicians contacted.

For a good chunk of time during the fundraising for Big Mamie, Edward Palmer’s car was adorned with an actual size replica of a 16” shell fired from a battleship with the words, “Save Big Mamie” written across it and the car itself. According to Jeffrey Palmer, Edward’s son, and Reading resident, Edward made it out of styrofoam, black electrical tape, red tape, and white letters. Although Jeffrey’s brother and mother weren’t big fans of having a “bomb” sitting on top of their car, Jeffrey was definitely a fan.

On June 12, 1965, with the help of a handful of tug boats, Big Mamie was towed up Narragansett Bay to Fall River. Thousands of people lined the shores and bridges to cheer her on. The USS Massachusetts was coming home. She was dedicated on Saturday, August 14, 1965, and to this day, is docked in Fall River in a place known as Battleship Cove. From the waters off Casablanca, where shells whizzed overhead and death rained from the sky, from the waters of the Pacific, backing up our boys on the ground, to the safe waves of her home. Edward Palmer was just one of the men who helped bring Big Mamie home, but without his hard work, creativity, and perseverance, there might not have been a Battleship Cove, and the USS Massachusetts might not still be around to teach us the lessons of the past. In 1980, when the battleship was desperately in need of repairs and maintenance, her former crew volunteered their skills and time to help her. The men who did this were repaid by Big Mamie: they would walk about and return to the very same battlestations and posts that they had occupied just fifty years before. The same way you or I might feel some sense of nostalgia when walking through the hallways of our old middle school or high school, these men felt the pull of time as they ventured around the ship they had called home for so many months, all those years ago.

On April 15, 2003, Edward Wallace Palmer, of Stoneham, and later, 45 Pratt Street, Reading, Massachusetts would pass away. His legacy is not only continued and upheld by his children but by that magnificent work of American industry that rests in Battleship Cove, called the USS Massachusetts.